Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Death and Political-Economic Fragility in South Asia

September 15, 2022 2022-09-15 17:24Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Death and Political-Economic Fragility in South Asia

Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Death and Political-Economic Fragility in South Asia

NESA Center Alumni Publication

By Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, Senior Fellow, The Millennium Project

15 September 2022

Political and economic dysfunction is an invitation for terrorism to flourish in the least integrated region in the world, South Asia. P.R Chari, director at IPCS India, captured this a year after the 9/11 attack in a paper called “Combating Terrorism: Devising cooperative countermeasures,” arguing that “the war against international terrorism must rest on two pillars, viz. a holistic approach to countering the threat by addressing the allied threats to international security and devising of means to secure cooperation at all levels- international, regional and national. These are linked issues.” South Asia, at the moment, requires a particularly holistic approach.

When the autocratic president Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled Sri Lanka this summer, he left a dangerous military footprint. Would-be autocrats, who constantly warned that the Sri Lankan uprising would end in chaos during their rule, had to prove that they were correct. The peaceful uprising on 9th July was systematically crushed by the military and the newly appointed president Ranil Wickremesinghe of Sri Lanka, Rajapaksa’s protégé. The ousted autocrat could use political resources and proxies to create more dysfunction on the island; the point would be to convince Sri Lankans that life in the past was better and that his political return could restore it. Gotabaya’s victory in the 2019 presidential race was based on a similar appeal: in the wake of the Easter Sunday Terror attack, he guaranteed security and justice for the victims.

In nearby Pakistan, ex-prime minister Imran Khan has said, “We are not far from Sri Lanka moment when our public pours out into streets.” Both Khan and Rajapaksa lost their positions in the same month. Other South Asian nations have telltale signs of political dysfunction, too: rampant corruption, arbitrary detention, militarization, human rights abuse, and worse economic conditions. A safe haven for terrorism is set to flourish.

We must be careful with our analysis. Ethnic and religious divisions, for example, have not played a substantial role in Sri Lanka’s recent turmoil. This suggests an early sign of a coherent political ideology among the protestors. The Sri Lankan protest was effectively an Arab Spring moment. It had sprung up in protest against the same three problems that moved crowds in Tunis and Benghazi ten years ago – autocratic rule, rampant corruption, and economic stagnation. In 2011, these revolts ended almost uniformly in more dysfunction than before. The protestors would divide into bitter, warring camps and ideologies; some would rally to the Islamic State, while others became supporters of the kind of police states and illiberal government they had once marched against.

Today, as Human Rights Watch warns, Sri Lanka is just such a police state, with over three thousand protestors arrested arbitrarily under a draconian emergency rule. The other camp, the Islamist reaction, is incubating. The country’s present fragility is conducive to external terrorism, which devastated the country in 2019 and could resurface anytime.

Terrorism in South Asia and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Death

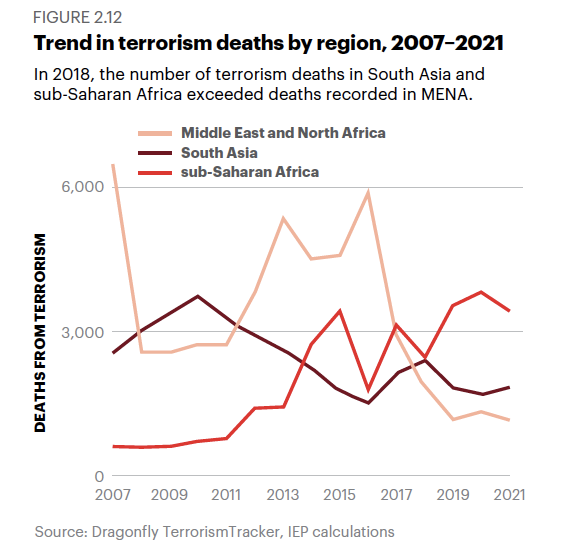

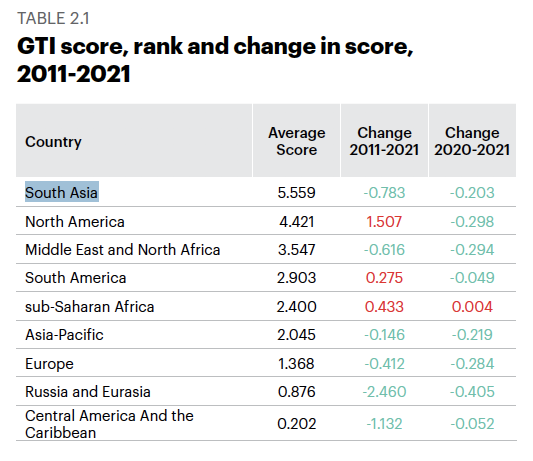

According to the Global Terrorism Index 2022, “South Asia recorded the highest number of terrorist explosive attacks in 2021 of any region in the world.” South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have recorded more terrorism deaths than MENA for the last three years (Figure 2.12). South Asia remains the region with the worst average Global Terrorism Index GTI score (Table 2.1)

Jeff Smith from the Heritage Institute rightly argues that despite the good news of the July 2022 assassination of Ayman al-Zawahiri, deputy of Osama bin Laden, there is also bad news. “One year after the chaotic [US] withdrawal from Afghanistan, Zawahiri’s presence in the capital of Kabul confirms fears that the country again would become a safe haven for international terrorists.” The precision strike on Ayman al-Zawahiri without any civilian casualties underscores the intellectual strength of the US to hunt any terrorist in hiding. Biden administration’s approval of a CIA-specialized drone-launched Hellfire missile strike – the first since the American exit from Kabul a year ago sent a clear message to nations providing safe refuge to terrorist leaders.

One week after Zawahiri’s death, Abdul Wali, also known as Omar Khalid Khorasani, was killed. It was a major blow to his armed group, known formally as the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Khalid Khorasani had carried out some of the deadliest attacks in Pakistan, including the Easter Sunday attack in 2016, killing 75 people from the Christian community. It was believed that he was close to Osama bin Laden and al-Zawahiri. He had a more tenuous relationship with IS.

On 29th April 2019, six months before IS leader Abu Bakar al Baghdadi’s assassination, the IS chief appeared on his last video message claiming responsibility for the Sri Lankan easter Sunday terror attack, which killed 258 innocents. Member state UN investigations revealed that the IS did not, in fact, direct or facilitate the attacks, nor did it know about them in advance. The UN Security Council report reads, “In a video message in late April 2019, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi confirmed that ISIL still aspires to have global relevance and expects to achieve this by continuing to carry out international attacks. The group is currently dependent upon ISIL- inspired attacks, such as the Easter Sunday bombings in Sri Lanka, which Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi mentioned but which ISIL leadership clearly knew nothing about in advance.”

Clearly, locally inspired independent terror cells and their South Asian proxies remain, even if the terrorist leaders are killed, and main groups are dismantled. It was clear from Ayman al-Zawahiri’s death that Al Qaeda continues to cooperate closely with the Haqqani Network. Zawahiri was living in a Kabul guest house owned by Sirajuddin Haqqani at the time of the air strike.

There are four critical takeaways for South Asian leaders in the wake of the Zawahiri attack.

First, the weakening of the al-Qaeda network has forced violent extremist groups in Afghanistan to go underground, decentralize, and join independent jihadi terror cells operating abroad, especially in other South Asian nations. Dysfunctional states like Pakistan and Sri Lanka will be lucrative grounds for this activity. Intelligence operatives, financiers, logisticians, couriers, and recruiters will sustain it. Since Afghanistan is cut off diplomatically from the West and ruled by an internationally unrecognised regime, addressing the longer-term counterterrorism in the region will be much more involved than the one-off kill of a single man.

Second, the single biggest success of the United States in Afghanistan was the US Special Operations Command (SOCOM) in over-the-horizon operations to take out most of the al-Qaeda leadership. But the capacity to deploy without ground resources and directly hit the terrorists at will can lure the US into a false sense of security. Washington should fix the limits of its over-the-horizon counterterrorism engagement, such as the absence of local partners and operational support. The limited reach of local engagement should be quietly expanded with a redefined and clear US-South Asia counterterrorism strategy.

Third, Washington should take strict measures against nations that safeguard terrorists and publicly question if those nations are living up to their counterterrorism commitments. At present, while the Taliban and US bicker, the former has guaranteed that Afghanistan would not harbour anyone who violated the 2020 Doha Accords. The United States, in turn, has assured them support for counterterrorism against al-Qaeda and the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-K). Commitments may be tricky to uphold, but it’s not an impossible task, and Washington must insist on it.

Finally, building trust in the region is key. According to Major General Mahmud Ali Durrani (ret.), in his paper on finding a common denominator to fight terrorism, “The fundamental challenges to fighting terrorism, especially in South Asia, are the existing differences between various nations and the presence of serious mistrust due to the ongoing conflicts.” A common denominator is the absent, critical ingredient for coordinating the counterterrorism strategies of the many South Asian nations. Multilateral engagement should be strengthened. Sreoshi Sinha is right to argue that strengthening the multilateral agenda is “an option for nations like India to collaborate with the US and lobby for Washington to be admitted as an observer state to the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC).” Terrorist networks and modern economies have this much in common that they are international affairs. Fighting one and building the other – the two faces of the same South Asian coin – cannot be Washington’s job, or Delhi’s, or Colombo’s. Every country’s discipline and perseverance count, and every weak link, every autocrat, weakens the chain.

The views presented in this article are those of the speaker or author and do not necessarily represent the views of DoD or its components.